By Gary Grube, Friends of Petrified Forest Board Member

English rocker Rod Stewart’s 1971 hit taught us that “every picture tells a story.” Petrified Forest National Park has tens of thousands of pictures on rocks left by indigenous inhabitants of this beautiful place, but we lack the vocabulary to interpret their stories.

Rock art abounds in the park, primarily in the form of petroglyphs. While we cannot be certain of the meaning and purpose of prehistoric images, we can be reasonably certain the meanings and purposes were many and varied. Could some of these not be merely people’s signatures (ancient Puebloans must have had names and ways to represent them) and mean nothing more than “I was here”? By 1450, these rock artists were no longer here, and the boulders and cliff faces lay fallow for centuries.

Folks who arrived later conversed in languages we do understand but bequeathed us only a few names and a few dates – but no pictures. Does that mean they had no stories? No, it means we need to work harder and search deeper to elucidate their stories. I’ve done this, and learned they were a motley lot who came to this area with countless backgrounds in countless places for countless reasons. By making their marks here, they melded their stories with that of the Park.

Here are images of some of these interesting historic inscriptions. It is not comprehensive. It is only marginally fact-checked. I am is a hiker and a huge fan of Petrified Forest, not a scholar. My hope is to coax you to come to explore this wondrous place, leave your vehicle, come explore for yourself, and maybe you will also find a bit of history as I have.

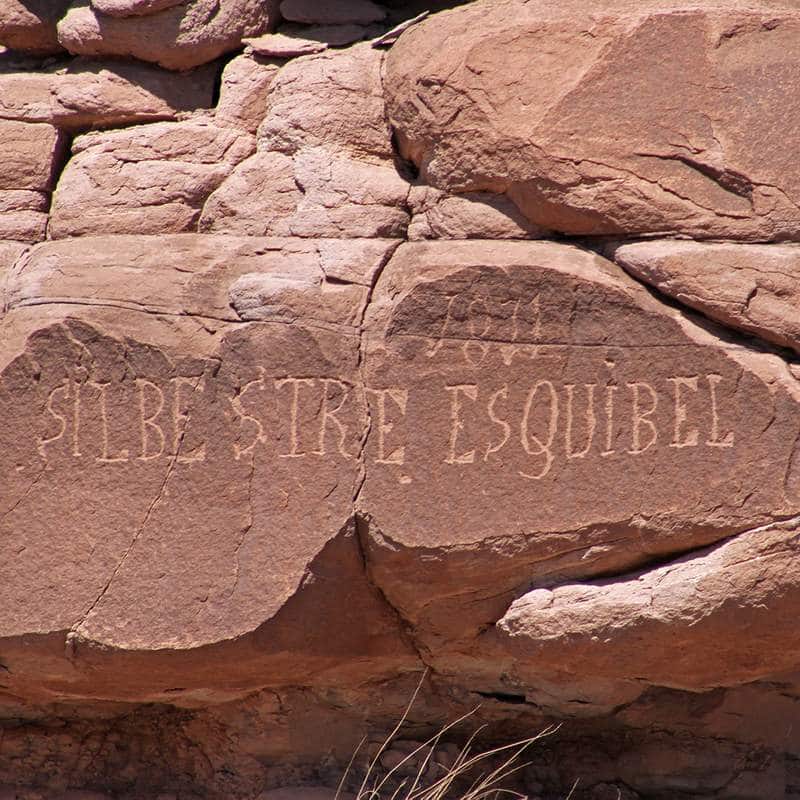

In 1811, Silbestre Esquibel came this way and tarried long enough to carve his name near Lithodendron Wash. In the same year, Santa Fe merchant Jose Rafael Sarracino traveled to central Utah to investigate trading potential with the Utes. Painted Desert is hardly along the shortest route from Santa Fe to Provo, but if Sarracino followed the track of the 1776 Dominguez and Escalante expedition, he would have passed through the current Petrified Forest National Park, and Silbestre Esquibel might well have been with him.

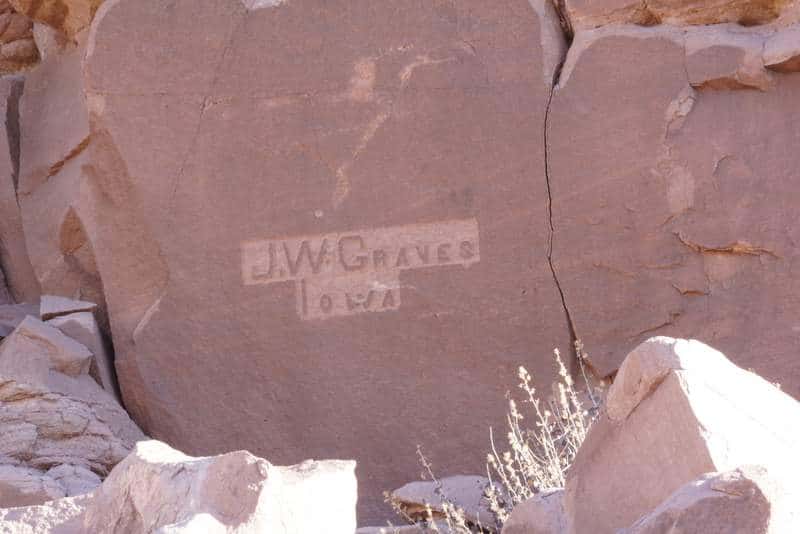

The inscription of Iowan J.W. Graves is exceptional in that it was embossed rather than engraved. This must have been quite time-consuming. For his effort, Graves chose a cliff face near a now derelict stagecoach station. Perhaps he was an employee there with free time between coaches, or a passenger with an unscheduled layover. If so, it would have been prior to 1881 when completion of the railroad just a few miles south supplanted stage service.

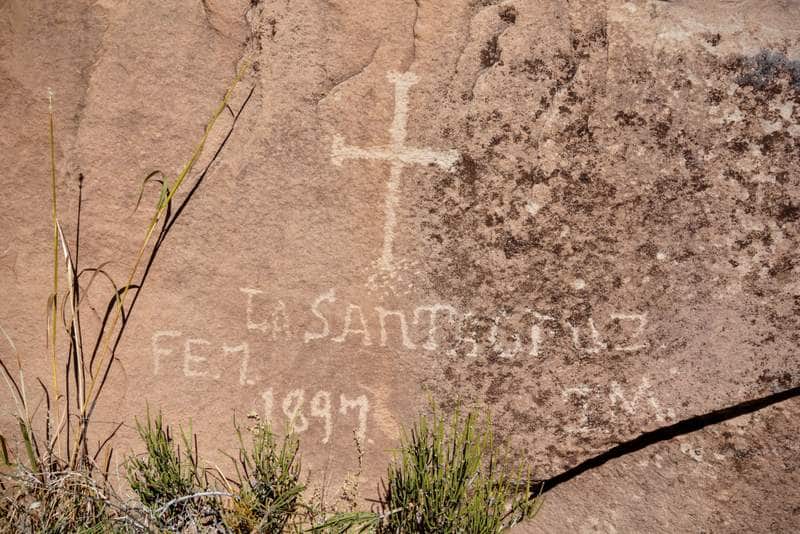

By February 7, 1897, when L. Santacruz and T. Miera left their marks, ranching was well established in the area. Cattle and sheep grazed and overgrazed the land that would become Petrified Forest National Monument nine years later. Santacruz and Miera may have been shepherds from the Basque community of Concho not too far to the south.

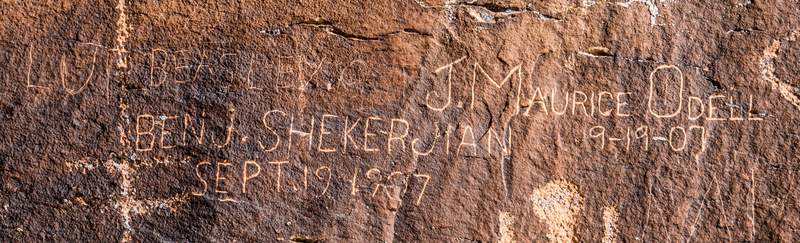

Petrified Forest was only a year old in 1907. Most visitors from afar traveled here on the Atchinson, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway, alighting at the small town of Adamana. The monument itself was still some miles and a rough buggy ride south. Just a mile east of Adamana, however, was another tourist attraction – a major archaeological site. On September 19, J. Maurice O’Dell and Ben J. Shekerman went there, perhaps on foot, and carved their names on a large boulder already replete with ancient petroglyphs.

Something about that boulder beckoned scribblers, and years later Luther “Lut” Beasley appended his name to those of Shekerman and O’Dell. Luther was a local, a resident of Adamana born in 1905. Over the years he graced many rock surfaces with his signature, and he resides now in Chambers, Arizona, beneath yet another stone bearing his name, in McCarrell Memorial Cemetery.

Solomon Sanchez found himself at the base of a Painted Desert mesa with time on his hands in May 1925, so he took out his knife and engraved his name on a boulder. “Chiseled in stone” can mean definite and enduring. Lichen is dissolving Solomon’s signature, which definitely will not endure another century. Interestingly, Holbrook cemetery records indicate a Salomon Sanchez lived in the area from 1909 to 1943. Might Salomon be Solomon with a typo?

Until 1932 when the current park highway was constructed, visitors arrived via rail or nascent Route 66 and followed a dirt track from Adamana to park headquarters in the south. The final few miles of that route were the stream bed of Jim Camp Wash, the surface of which could vary from deep, loose sand to sucking mud to something in between that was occasionally drivable. We can imagine an early vehicle, bogged to its axles in the wash, and the driver and passengers rendering names and initials while waiting for assistance to arrive.

On Monday, April 29, 1935, a bench-clearing brawl interrupted the game between the Cubs and Pirates. Chicago eventually won 12-11. Victor and Lena C. and friend Frank B. would have been unaware, absorbed as they were in decorating a boulder north of Whipple Point. It was a popular location: Someone else incised a fine little kachina figure, just visible on the left end of that panel; and a nearby boulder displays large crudely pecked figures, one a Hopi maiden, on two sides.

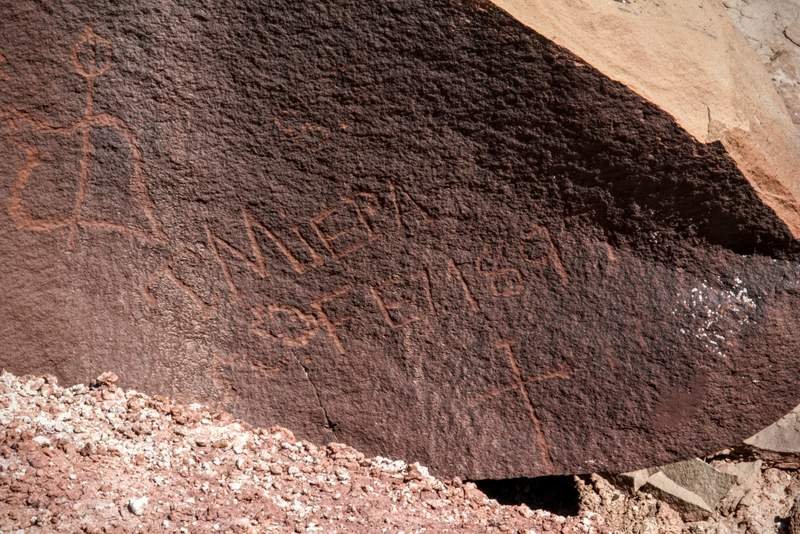

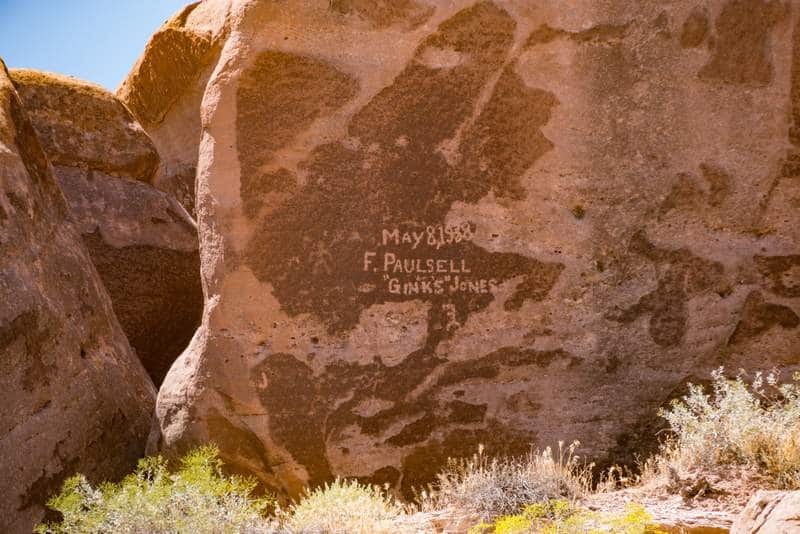

In 1917 J.C. Paulsell, originally from Missouri, bought a ranch on the monument’s eastern border and moved his wife and children there. On a Sunday 23 years later, young Frank Marvin Paulsell and compatriot Ginks Jones pecked their names into a cliff overlooking Lithodendron Wash near the western boundary. Petrified Forest National Park acquired much of the Paulsell ranch in 2004 after the authorized boundary had been expanded by Congress.

Arthur “Art” Beasley, older brother of Luther, was another local boy who affixed his name to geology in the area. Art gathered petrified wood which he sold to passengers on the trains that steamed through Adamana. He eventually set up a rock polishing shop and added curios to his wares. Art married Anna Yellowhorse, a Navajo woman, and they had six children. The family-operated curio stands along major tourist routes, and they eventually realized the Yellowhorse name would attract more trade than Beasley. The flagship outlet, Chief Yellowhorse, still operates along I-40 in Lupton on the Arizona/New Mexico border.

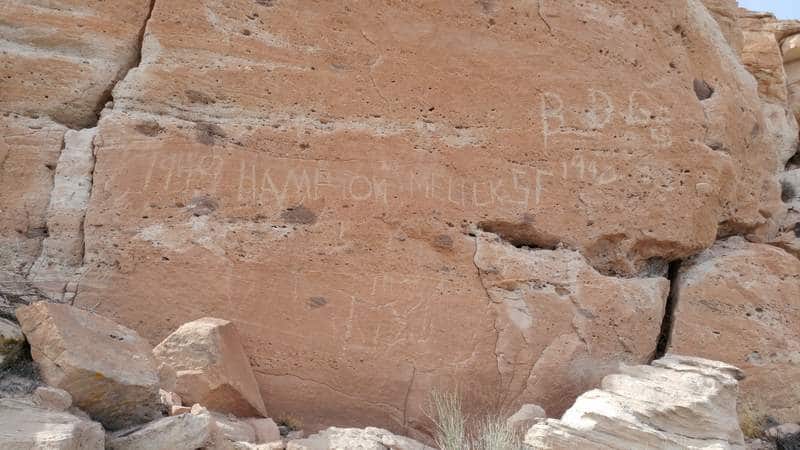

Like Ozymandias, Hampton Melick (from San Francisco?) may have sought immortality by affirming his being in stone. In 1940 he boldly scratched his name on a cliff face overlooking Cannon Rock, a geologic feature and tourist photo op at the base of Agate Mesa. Alas, the rock fell, and hardly anyone goes there anymore; and even if they do they won’t notice Hampton’s handiwork, for tall brush makes it nearly invisible from ground level.

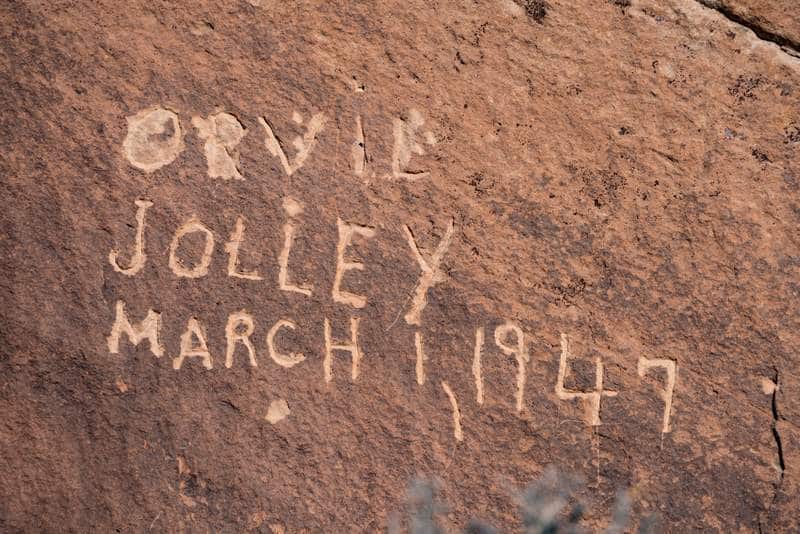

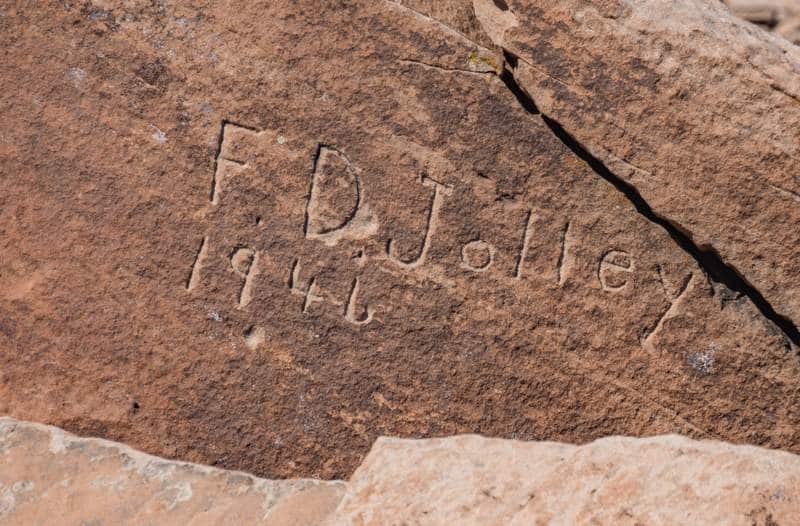

Many older structures in PEFO were constructed of native stone quarried near the building sites. One such quarry is just a couple miles inside the Park’s south end. It is there that Orvil Lionel and Ferris Delbert Jolley from St, Johns left their calling cards. Ferris called first, in 1946. On a Saturday the following year, Orvil noticed his brother’s name and added his own. But why were they there at all?

Between 1934 and 1942 the Monument hosted thousands of Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) participants. These were able-bodied young men (many were boys in their teens) with lots of downtime and access to stone-working tools. One might expect them to cover every available flat surface with petragraffiti, but they didn’t. The few inscriptions they left are chaste, unobtrusive, and brief. One sometimes wishes for more information.

Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, ostensibly starting World War II. Before three more years passed, many young park workers, a large portion of whom hailed from Pennsylvania, would transition from CCC to military service. On that fateful Friday, C. Janicki, whose surname is Polish, probably took no notice. He was busy affirming his existence on a remote boulder. Janicki may have borrowed the cross figure from the nearby 1897 glyphs of Miera and Santacruz.

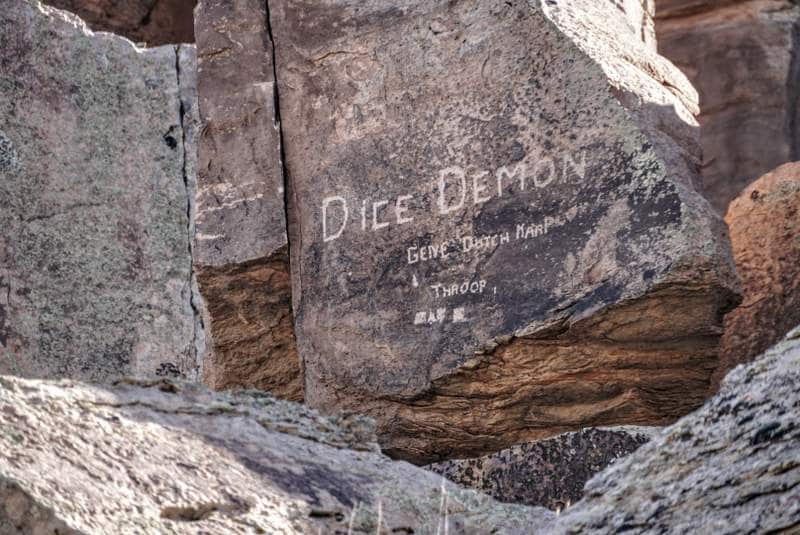

CCC workers were paid $30 per month, of which they were allowed to keep $5, the remainder being sent home to their families. It’s not difficult to guess what Gene “Dutch” Karp from Throop, PA, did with his $5.

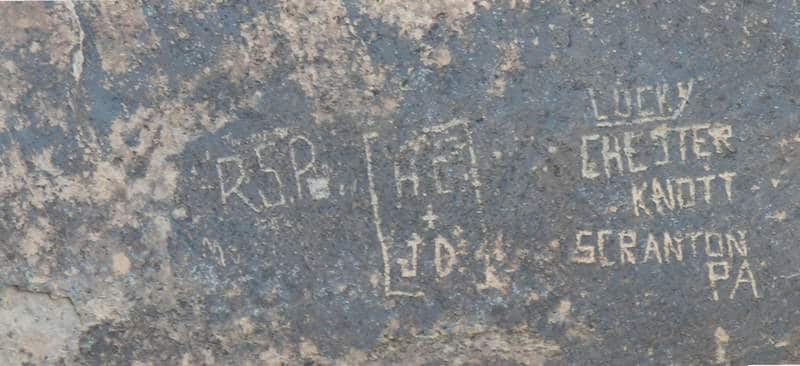

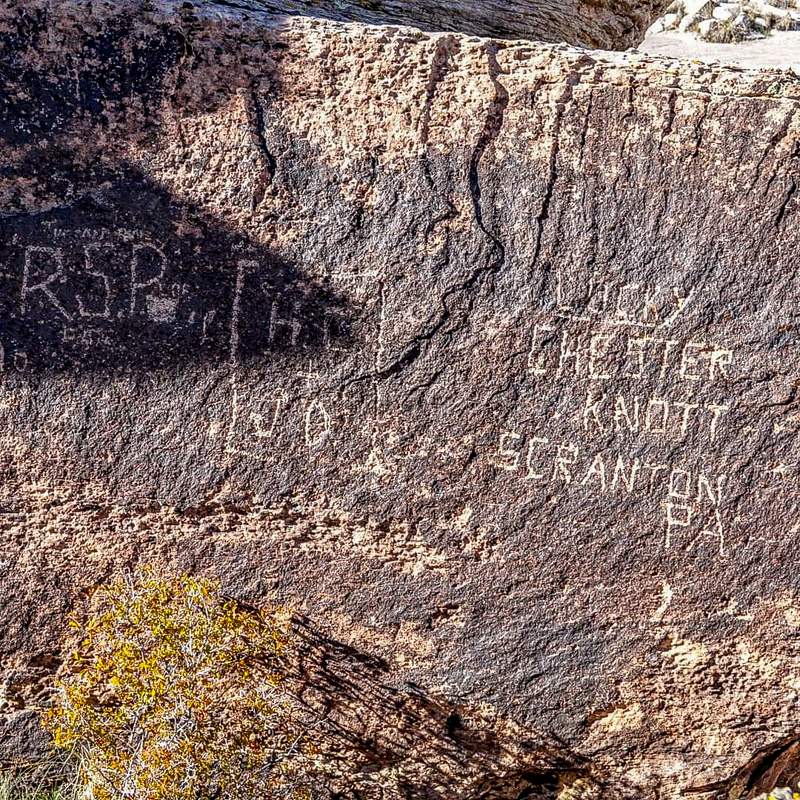

Scranton’s Chester Knott may have been Lucky, but was he lucky when he rolled with Dutch Karp?

M.V.F. Most valuable friend? Were Henry and Rosendo both Perezs? Were they brothers? Cousins? Lovers? We want to know more.

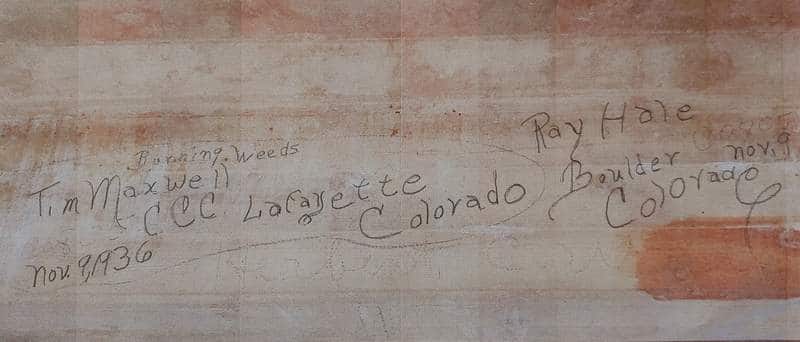

Shortly after midnight on Monday, November 9, 1936, actors John Barrymore and Elaine Barrie wed in Yuma. Later that day, 390 miles away and far from Hollywood, Tim Maxwell and Ray Hale from Colorado burned weeds at Petrified Forest. We know because Tim and Ray left us a message, written in charcoal, beneath a bridge along the park highway. The inscription is unique on several counts: The amount of information it contains; being a pictograph, not a petroglyph; and appearing on the manufactured rock (concrete) instead of natural sandstone.

Another unique specimen lies just a mile away: a heavy wood beam in a place where no beam has reason to be. Exposed to the elements for 80 years, the inscription carved on it is fading but discernible, barely. On the right, someone incised “PROLL” (a person’s name?), “NOV *4” (34?), “PHILA”. In the center, the word “EAGLE” is still obvious, and to the left of it is a five-pointed star inside a horseshoe-shaped figure. A football helmet? But the star is inconsistent with Philadelphia Eagles. Again, we want to know more.

Most park rock art is modest in size, but on a rarely visited plain in Petrified Forest Wilderness lies an image so large it is visible from space. It is a letter, either “P” or “d”, formed in large stones. You can see it for yourself on Google Earth at 35.086456, -109.81517. Is this an “I was here” message, and if so, who left it? For the record, Park Chief of Science and Resource Management Dr. William Parker denies any knowledge of this geoglyph.

While creating durable rock art within the park (and monument before it became a park) was never encouraged, it has become less acceptable with passing time. Today, it is not just actively discouraged, but completely forbidden and illegal. Significant inscriptions after 1947 are rare. Early visitors traveled at a leisurely pace and could linger long enough to carve or peck a name. These days, Petrified Forest is a drive-by experience for most folks, who want to fit Petrified Forest, Grand Canyon, and Meteor Crater into a single day. We find their inscriptions in the only place people still tarry: the restrooms!